The case of Taylor v Jaguar Land Rover has been trumpeted as a “landmark” employment tribunal decision recognising that people who identify as non-binary or gender-fluid can be covered by the Equality Act protected characteristic of “gender reassignment”.

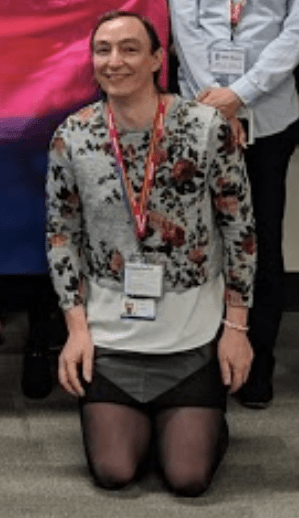

The case concerns Mr/Ms Taylor, a man who began to wear women’s clothing to work in 2017 as part of a process of exploring his gender. He now identifies as a transwoman. He can be seen here being interviewed by Pink News at the time:

The tribunal seemed particularly keen on inhabiting the role of landmark decision-makers, going into a soliloquy about individuals who make a difference including Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King and Ruth Bader-Ginsberg (“The Notorious RBG”, as they noted).

But there is a lot less to the landmark part of the decision than has been promoted. It was already clear that the protected characteristic of “gender reassignment” in the Equality Act is very broad, covering people from the moment they first let it be known they are considering transitioning. Nothing has changed here from a legal point of view.

More interesting are the real-world specifics of what happened. What were the complaints? What did Jaguar Land Rover do? What did the Employment Tribunal think they should have done differently?

A Rose by Any Other Name…?

Legal questions about trans rights and women’s rights are often articulated as being about competing rights. This is a useful framework. But it sits on top of another one, which is even more fundamental to justice: “the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth”.

The Equal Treatment Benchbook, which guides judges’ conduct, says:

It is important to respect a person’s gender identity by using appropriate terms of address, names and pronouns.

Equal Treatment Benchbook

But what if following this guidance means the court loses sight of reality itself?

Taylor was still known by his male name Sean during the course of his employment, and was referred to using male pronouns by colleagues and bosses. He put information about his two identities in the public domain in a media interview in 2017. Yet the judgment uses female pronouns, throughout including when quoting documents and statements from the time. This makes the whole judgment misleading, and results in nonsensical statements such as

the Claimant had for some years considered herself to be a gay male.

Judgment

For clarity, this article uses male pronouns and the name that Mr Taylor was using at the time, as it is important to reflect how colleagues and managers would have experienced reality.

What happened

Jaguar Land Rover is a male dominated company. Women make up 1 in 10 of the workforce. With 50,000 staff in the West Midlands, it is the region’s largest employer. Sean Taylor had worked at Jaguar Land Rover as an engineer for 20 years. He was based at Gaydon – a complex with some 13,000 staff; the size of a small town. In the building where he worked there were over 1,000 people.

In March 2017 Taylor told HR that he was transgender and thought himself to be on part of a spectrum, transitioning from the male to the female gender identity. He said he wished to dress in a male style on some days and a female style on others. Over the course of the next year he got some comments and stares. There was also a long-running conversation with local management over toilets.

The case against Jaguar Land Rover was that in not protecting him from colleagues’ comments, and asking him at one point to use the accessible unisex toilets, they engaged in a course of harrassment and discrimination.

The harassment

Harassment in the Equality Act is defined as “unwanted conduct related to a relevant protected characteristic, and which has the purpose or effect of violating a person’s dignity, or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment”.

The core of the harassment allegations was around a dozen comments from different people over the course of a year, which Taylor kept a log of in his transition diary.

The majority of the comments that the tribunal judged to be harassment seem to reflect people trying to acknowledge Taylor’s new appearance. While some of them are awkward, and it is impossible to judge the tone or intent from the words alone, the sentiments mostly appear broadly well-meaning:

- A male colleague: “In Gaydon today and noticed the great outfit”.

- A male colleague: “Are you not fem today?” He went on to say that he had trans and lesbian friends and that the Claimant was “very brave”.

- A female colleague: “I was checking out your dress, saw it was you and my jaw dropped”.

- A male colleague: “How do you get around in them? It looks hard work.” [presumably referring to shoes]

- A female colleague: “It’s nice to see you here in your attire. You have cracking legs”

- A female colleague: “Don’t take this the wrong way, but I saw you as the top half and it didn’t match the bottom half” followed by an email which said: “(and perhaps I shouldn’t put this in an email), I think you’re beautiful and standing talking with you very much increased that perception” followed by a number of smiley faces .

A couple (involving the same male colleague) were discussion starters on trans politics, which may have been experienced as hurtful:

- “What do you think of trans versus TERFS? I don’t think trans should use female spaces until they have the op”.

- The trans community ought to be grateful. Some of their antics have nearly damned near turned me TERF.

A couple were expressions of surprise by people he passed in open common areas (including at other sites in the region):

- “Oh my God!”

- “Oh my God. Wow!”

One was hurtful direct banter:

- A male contractor (on October 31st) “Is this for Halloween?”

One was a hurtful overhead conversation:

- Two male colleagues in the toilets – “Have you seen it”? — “I saw ‘it’ in the atrium”.

One was an inappropriate and intrusive question:

- A male colleague: “So what’s going on? Are you going to have your bits chopped off?

In addition a lorry driver beeped his horn, and Taylor felt a male colleague had stared at his legs.

In another incident a manager laughed at the suggestion that he wear a rainbow lanyard (which was amongst a list of 50 actions for demonstrating allyship Taylor had presented) – “No more!” remarked the manager, and said that he had a job to do.

When Taylor complained about these incidents he was asked to give details so that allegations of harassment could be dealt with. He declined to do so. The tribunal called these comments “a sustained course of wholly unacceptable harassment in the workplace” and said that Jaguar Land Rover should have issued a notice highlighting “‘serious concern’ of unacceptable harassment due to protected characteristics”, drawing on its Dignity at Work procedure.

The Dignity at Work procedure highlights “name calling, using very inappropriate names, banter, practical jokes, suggestive comments, abusive language, jokes, posters, assault, insulting behaviour or gestures and circulation of offensive material including the use of email.” While a few of the comments were of this character (calling someone “it” for example) it’s not at all clear that most of them were.

The Employment Tribunal seemed willing to backfill the definition of harassment to cover anything that Taylor found upsetting. But it is hard to see how Jaguar could have communicated this to its thousands of employees Perhaps they could have put together an edict, possibly with Taylor’s input with examples of unacceptable conduct, but trying to find the right line that would have prevented all such comments would have been difficult.

The toilets issue

On 24 May 2017 Taylor met with his manager Mr Poole and made a powerpoint presentation about transitioning. During this meeting Mr Poole said that Taylor should use the disabled toilets. It’s not clear whether this meant he was being told he should not use the male toilets (but it appears unlikely); more likely, he was being told that he could use the disabled toilets if he did not feel comfortable using the male toilets.

On 16 June 2017 HR sent advice to Mr Poole, saying:

The watch outs are toilets, which ones will [Sean] be using, please don’t request that he uses the disabled toilets as this puts us straight in the firing line on the discrimination front. If this becomes his own decision at some point, that’s fine.

On 16 July 2017 Taylor wrote to HR saying he was not sure what the toilet arrangements should be.

On 19 September 2017 Taylor sent an email to a manager, saying: “I don’t know what toilet to use, I raised this three times with no progress over six weeks. I spoke to HR twice about moving as part of the transition at work, but this was ignored.”

On 11 October 2017, in a grievance meeting, Taylor again raised the toilet issue, saying: “I am transgender, and I struggle with what toilet I should use…I understand it is difficult to resolve but I am not having any feedback and who will fix it?”. The response was that HR must make a clear and unambiguous statement quickly.

Finally, following on from the grievance meeting there were a series of discussions between local management and HR, and it was decided to allow Taylor to use whatever toilets he wanted on any given day:

while the company considers whether a suggestion such as gender-neutral toilets would be appropriate, we feel you should use the toilets you feel comfortable to use each day. We appreciate this will vary from day-to-day. However, if you do not feel comfortable using either the gents or the ladies, then please use the disabled toilets.

The tension between the exception applied to Taylor and the general rules of the company quickly became a problem. Taylor complained that the women’s toilets were locked (with a code) in some locations to avoid vandalism, and this caused him stress. He was concerned that trying to gain access to the women’s toilets would involve “difficult conversations with local staff”.

The Tribunal said that allowing Taylor the choice of which facilities to use “put the onus on the Claimant to decide which toilets to use and to deal with any challenges made by colleagues unhappy with the choice”. It said that Jaguar Land Rover should have put in place measures to “prevent her having to deal with challenges over the toilets she was using”.

The tribunal suggested “putting out a message to inform relevant staff which toilets the Claimant would be using”. This does not seem practical. What were they supposed to do? Put photos of Taylor in all the women’s toilets across the region? And what if women objected when told that a man would be using the women’s toilets?

The other (more sensible) option the tribunal suggested was “designating some sets of toilets gender neutral”. But it stated that using the existing unisex accessible toilets for this purpose was not appropriate:

Telling a transitioning person to use the disabled toilets is, at the very least, potentially offensive to them because it suggests that their protected characteristic equates to a disability. Secondly, disabled toilets are for disabled people to use and should not be used by other people.

Tribunal judgment

In fact the Equality and Human Rights Commission notes that Gender Dysphoria can be classed as a disability (although in this case Taylor did not have a diagnosis). More broadly, while employers must provide sufficient toilet and washing facilities to allow everyone to use them without unreasonable delay (including workers with a disability) there is no requirement that accessible facilities be strictly restricted to those with a disability. In Croft v Royal Mail, the Court of Appeal had found that unisex accessible facilities can be appropropriate provision for someone who is transitioning.

Rules and reality, or wishful thinking?

The employment tribunal was keen on grand gestures – comparing Taylor to Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, and rewriting history so that the events it considered appear to relate to a woman called Rose, rather than a man called Sean. They refer to Taylor, a man in his 40s, as a “poster girl for LGBT+ rights”.

They are less keen on the idea of occupational health support for Taylor’s mental health issues, including self-harm and suicidal ideation, saying these were only the symptoms. They diagnose the way Taylor was treated by colleagues as the cause of his distress, apparently without the benefit of any expert evidence.

It is notable that Taylor began the “social transition” to dress in women’s clothing at work without any diagnosis, or medical or psychological support. His mental health seriously deteriorated. A therapist might have been able to better prepare him; helping him to anticipate how colleagues might respond, and supporting him to develop resilience strategies for when those responses did not align with his inner world.

The tribunal’s enthusiasm for playing along with the fantasy meant that it failed to consider the practical dilemma faced by Jaguar Land Rover, namely, where there was a mismatch between Mr Taylor’s self-perception and material reality, what exactly should the company have done to protect him from feeling distress at how others perceived him? What rules should it have communicated to all employees?

The tribunal was scathing about Jaguar Land Rover’s handling of the situation, saying:

It is fair to say that the Human Resources Team has not functioned properly or provided accurate and professional advice in this case.

Certainly Jaguar fumbled the toilets question by being unwilling to say “no” to a male employee with a strong desire to use the ladies.

But the tribunal itself tried to close off the practical solution of allowing Taylor to use the disabled toilet where other gender-neutral options were not yet available. Its conclusion does not appear to have any basis in law.

And its suggestions do not engage with the need for clear, fair rules in large organisations. Should all comments related to colleague’s clothing be strictly forbidden? Should anyone be allowed to use any toilet they choose, regardless of their sex?

Or does the tribunal believe that Jaguar Land Rover should have applied special rules to Mr Taylor? If so, only on the days when he was dressed as in women’s clothes? Or does it believe that Jaguar Land Rover should apply special rules to anyone covered by Section 7 of the Equality Act? If so, how are colleagues supposed to know what these special rules are, and who they apply to?

Answering these dilemmas are serious questions for companies. Jaguar Land Rover should be cautious about letting Stonewall in if it wants to maintain a grasp on reality, and on the rights of all its staff.

One reply on “Taylor v Jaguar Land Rover: A landmark case, or losing sight of the landmarks of reality?”

Sex is a legally protected characteristic; therefore, it should count as sexual harassment of female staff for Taylor to enter the ‘ladies”. One wonders how desperate his desire to break the law, if he tried the door and complained when it was locked.

Disability is also a legally protected characteristic. To use disabled toilets when others are available denies access to disabled employees. That’s discrimination on Taylor’s part – again.

Meanwhile, when I was a young office-worker, I was expected to tolerate having to free myself from gropers at the filing cabinet, wolf-whistles, comments on my appearance, pats on the bum when walking past male staff, hand-gestures and tongue-licking gestures – just for being female.

This man behaved like a spoilt brat.

LikeLike